DENITA ELLIOTT/PHOTOS BY DENITA

DENITA ELLIOTT/PHOTOS BY DENITA

By Matt Fisher on August 2, 2012

__________________________

February 8, 2012

A sudden turnover by the visiting Dillon Wildcats instinctively sends a jolt of adrenaline through Dejan Frasier’s 5’11” frame.

Waccamaw only needs one win to clinch a playoff spot, and the Warriors are behind early in the first half.

So Dejan takes off down the left sideline, curls back toward the front of the basket.

And the ball – dark orange with a spiraling swoosh logo – flies over his right shoulder, falls softly into his hands. The Wildcat defenders have no chance of catching him.

They all watch helplessly. Watch the tight-knit dark-red No.32 on the back of his jersey, firmly tucked in at the waist. Watch Dejan plant his left foot, lay the ball on the glass.

Then the once-raucous Waccamaw crowd – Dejan’s crowd – goes silent.

The only audible sounds – the ball smacking the shining hardwood after softly falling through the basket.

And the screams. Dejan’s screams as he swirms crumpled on the floor.

It’s over.

Larry Ferraro pulls his eyes off the tally marks he just scribbled on the box score next to D. FRASIER, tosses the brown clipboard on his black seat cushion, and like Moonlight Graham from

Field of Dreams, he steps over the black sideline and shifts from coach to medic.

Dejan cocks his head back and faces the ceiling, gripping his left knee. He glances at it, then sticks out his neck and winces from the excruciating pain.

Ferraro kneels on Frasier’s left side, intently massages the knee while head coach Mike Quinn–eyes wide open in disbelief and at a loss for words – kneels on the other side.

“Is it bad?” Dejan asks, shades of optimism, despair.

Ferraro pauses. He’s seen a multitude of ACL injuries in his 33 years of medical practice.

“It’s semi-bad,” he says, hesitant to break the news, as if his delaying might cushion the blow caused by the truth. “You’ve probably torn it.”

You’ve probably torn it.

Dejan lies on his back, looks up at the blinding fluorescent lighting, covers his face with his forearm. Hope drowned out by the tears, tears those four dreaded words bring.

You’ve probably torn it.

************************************

Five years before the injury, August 2007

Dejan Frasier turns off his alarm clock, swings his legs out of bed. The sun’s not up.

He turns to the small electronic box on his nightstand, squinting his eyes to read the time displayed in vibrant red digital numbers: 6:00 A.M.

|

| Dejan spent early summer mornings at Hartford's Sarah J. Rawson Elementary. |

|

Anxiously sliding into his high tops, he flies out the front door and walks a few blocks down the street towards the

Rawson Elementary School playground, where he goes to shoot around and play games of twenty-one with his best friends – Jerome Harris and Anthony “Ant” Jernigan.

His shoulders low, Dejan dribbles to his left, steps back, and bends his knees to elevate behind the arc for a three-pointer. He holds his follow through, watching the ball spin through the white netting. Then the swoosh, a sound so familiar to his ears.

Dejan repeats this routine every summer day – constantly practicing in the early morning, getting up shots while bouncing around on the smooth gray surface of this small outdoor court in Hartford, Connecticut.

Hartford isn’t the safest city – in fact, its

violent crime index is 597.2, dwarfing the national average of 259.7. Safer than just six percent of cities in the U.S.

But it’s home for Dejan.

Just like the court – firm and solid beneath him.

He knows what the next four years hold – attend Hartford’s own Weaver High in the fall, join a squad that concluded a 22-3 season with a state championship just the year before.

And he’s not just practicing every day in the summer on this court either. He’s a member of the

Connecticut Basketball Club (CBC) Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) team, playing alongside

Andre Drummond, the top-ranked ninth-grader in the country. Dejan’s the team’s sixth man, and last year, he helped them compile a 21-5 record playing against premier teams from across the country, including the

Dallas Mustangs, a squad that features Le’Bryan Nash and J.T. Terrell, two top 100 recruits in their respective future graduating classes.

The exposure from CBC is exciting for Dejan. His aspirations of playing in front of a Division I college crowd seem certain to be fulfilled in just a few years.

***********************************

Two years before the injury, February 7, 2010

The buzzer sounds, and Waccamaw’s basketball team members mob each other above Timberland High School’s green italicized

Tribe logo at center court.

The result shines in bright orange on the scoreboard – Visitor: 38, Home: 37. A first in Warrior history.

And while the team jumps up and down in exuberance, a No.21 Waccamaw jersey is nowhere to be seen in the gym.

|

| Dejan split time between the JV and varsity teams in his freshman season. | | | |

|

|

|

Because that jersey – Dejan’s jersey – didn’t make the trip. And neither did Dejan.

Dejan slouches on his couch and checks his phone.

Watching ESPN, he takes his eyes off the screen and fixates them on the text he just received from Tevin Gardner.

‘Bro we just won. I made the game winning shot.’

Dejan shrugs helplessly.

An 85? In Weight Lifting?

He can’t believe it. He isn’t allowed to travel with the team because of the borderline B in his physical education class. And according to Dejan, the grade probably should have been lower.

During his teammates’ jubilant celebration, he’s left sitting at home in disbelief and regret. It was an irresponsible decision, and he knows it.

Moving was a difficult transition for him – coming from an urban setting with great basketball roots – and falling into a small, geriatric, southern retirement area.

Pawleys Island, South Carolina – better known for what it

doesn’t have – a loud, city-like atmosphere – than for what it does. He misses everything.

The bond with his teammates during the AAU season. Playing games at the Basketball Hall of Fame.

He wishes Pawleys could be Connecticut Part II.

He sulks deeper into the couch, knowing he could have had more.

I would’ve had a ring by now.

A name for myself.

Few kids in his school realistically hold the same perspective he has for a future in college basketball. On the 700+ mile trip from Hartford to Pawleys, something must have been lost in between. And now?

He is – literally and figuratively –

on an island.

But it’s not moving that affects him the most. It’s that his irresponsible mistake has temporarily deprived him of basketball—his escape from the adversity that’s plagued him over the past year.

His father, Thomas Johnson, 36, was arrested for cocaine trafficking in 2008. It was Johnson’s second drug trafficking offense, and in the state of Connecticut, the maximum sentence can be up to 15 years. Johnson didn’t stand trial.

But his father’s incarceration doesn’t cause him to waiver from his responsibilities at home. Johnson didn’t play a large role in his Dejan’s life anyway. Five years ago, He and his twin brother Dyshan assumed the burden of helping their mother, Felicia Frasier, raise their baby sister, Buranda, while also looking after Riley, their other little sister.

For Dejan, shouldering the responsibilities in his household is like getting buckets – natural.

Responsibility fits well with his light-hearted personality. He’s the type of kid who smiles at people in the hallway – holding such charisma that you feel an instant comfort level with him even if you only met him five minutes ago. He doesn’t ask for commiseration or affection for his troubles. Nor does he want it; it’s just part of his persona. No excuses.

And point-blank, he

knows he’s more responsible than that 85.

*************************

A year before the injury, February 2011

Dejan shoots around in the gym at the end of practice on a cold winter weekday in Pawleys.

Not New England cold – but cold enough for a jacket.

He repeats the same motion over and over. Standing in the left corner, less than 20 feet away from the gym lobby, he shoots threes. Looking for the same rotation.

Same foot platform.

Same goose neck figure his left hand makes in front of his face when he releases the ball, his left arm fully extended.

And the same result.

He moves to the wing and takes several more shots.

The J.V. team stands in Coach Quinn’s classroom on the side of the gym opposite from the lobby, anxious to start practice. One tall jayvee leans out the door just in time to see Dejan rise up and swish a three.

“Damn, who’s that?” the tall jayvee says to another, recognizing him from one of his better games earlier in the season.

“Dejan Frasier, he leads the team in scoring,” the other dread-haired jayvee says.

The tall jayvee remembers seeing a previous game’s box score sitting on the table next to Coach’s desk.

He walks over and scans Dejan’s row in the spreadsheet, looking for his point total. But before he finds it, he spots a myriad of tallies in one column. 16 of them. He looks up at the top of the column, thinking that the number must represent points or rebounds.

“TO,” it reads. Turnovers.

Another jayvee looking at the same box score pipes up.

“If he didn’t turn the ball over so much, he’d be like mini Derrick Rose… or something like that.”

The team’s the laughing stock of the region all year. They have no chemistry, no signature victories. Entering the season finale, they’ve scrapped just three wins out of a less-than-daunting 19-game schedule. Eight losses by at least 17 points.

But while the losses sting, Dejan can’t worry about his team’s record. It’s all about the big picture.

And that’s why he repeats the same shooting motion, looking to get the same net-swooping result, and eventually – a different result on the scoreboard.

**********************************

Nineteen days before the injury, January 20, 2012

A half-hearted last-second heave falls short of the basket – and the clock hits zero.

Dejan gently untucks his jersey, purses his lips, sticks his chest out and walks to the handshake line – his eyes glued open. He tries not to look at the scoreboard while receiving “good game” consolations and pats on his back.

But out of the side of his left eye, it glares at him.

Visitor: 59, Home: 54.

He receives his last Marion High low-five and walks to Quinn’s classroom for a post-game speech, head down. In the semi-circle of plastic blue school chairs, he sits on the end farthest from the door. The players sit hunched over – some hands folded and heads hung, while others take arrhythmic deep breaths as they stare off into space. Noah Gulley, the tall and burly Warriors starting center, settles in a seat to Dejan’s left.

|

Chris Sokoloski/Georgetown Times

Dejan scored 26 points when Waccamaw hosted

Marion on January 3rd. |

“This guy right here,” he says, resting his hand on Dejan’s head, “played his heart out tonight. We wouldn’t have even been in it without him.”

Dejan scored 26 points in front of a packed house at The Tepee. He put out every ounce of sweat, dove for every loose ball, and left every single breath he had in his seemingly supercharged lungs in the cramped dimensions of that gym.

It would have been the greatest home victory in Waccamaw basketball history, beating a Class AA powerhouse led by a major Division I prospect in 6’6”

Marqui McKelvy.

But it’s just another crushing loss.

Despite it, the season hasn’t been a failure. Waccamaw defeated archrival St. James on the road a little over two months ago. The one-point victory was such a landmark for the program that J.V. coach Daryl Carr made a loud declaration amid the post-game celebration in the locker room.

“Waccamaw is now on the map!” he boomed, and the players followed it up with a collective “Yeaaaaahhh!” as they pushed and shoved each other in enjoyment.

But for Dejan, that game’s already in the rear view mirror.

It’s his senior year, and he’s running out of time.

He wants another shot at Marion. That’s the closest the school has ever come to beating the Swamp Foxes. Eight games remain in the 24-game season, and only a late run will grant them a playoff berth.

******************************************

After the injury, February 8, 2012

Another disappointing loss.

A tall African-American mammoth of a man with long dreadlocks – fittingly named ‘Tank’ – hunches over the scorer’s table he sits behind, and announces the score.

A 13-point Warrior loss.

He mutters a few more words over the microphone as the Waccamaw players and coaches shake hands with the Dillon Wildcats.

The team heads to Quinn’s classroom, having lost the final game of the season.

On the far side of the room, Dejan sits on a table, left leg stretched out and a wet ice bag on his knee.

Coach Quinn walks in his classroom and sets his blazer on a chair in front of his whiteboard. It’s his fourth season at Waccamaw. He coached prosperous high school teams in New York and North Carolina, before he came here for a new challenge, anxious to elevate a team buried at the bottom of the region standings for so many years.

He’s had to deal with disappointments like this loss along the way.

But tonight, he stands in the middle of the room, left hand on his hip, and runs his right hand through his black hair. Then sticks out his right arm, palm down, using it to guide his words of solace to the players.

|

DENITA ELLIOTT/PHOTOS BY DENITA

Quinn (center) came to Waccamaw in 2008 after coaching

Pawleys Island's private Lowcountry Day School since 2002. |

“Look guys, I know it’s tough… but it’s been a great season.”

Taylor King, a senior starting forward, interjects. “Coach, they just announced Aynor beat Loris.”

Quinn raises his eyebrows. “That broke the tiebreaker, we’re in the playoffs,” Taylor said.

“When?” Quinn wants proof.

“Tank said it right after he announced the score.”

Waccamaw had made the playoffs.

But even as Dejan sits on the table in the far end of the room, his slight smile masks the dark reality that’s already dawned on him.

He knows he wouldn’t play. His season is over.

*****************************************

August 2012

Dejan leans on his side at the edge of his hotel room bed, and pops the cap on a medicine bottle of

Osteo-Bi-Flex.

Then he tips the plastic bottle horizontal, shaking it for a few seconds until a small gel caplet falls on his hand. He pops the single pill in his mouth and takes a sip of water from a clear, thick-based hotel glass.

He’s at the University of South Florida on an official visit, the result of a 10-second one-sided phone call with NBA Hall-of-Famer and USF supporter Isiah Thomas.

On the bed across the room sits his mother, Felicia. He recalls Senior Night, when he and his best friend A.J. exchanged long embraces with her. At each of Dejan’s home games, it’s not too difficult to spot her in the crowd.

“Get the ball, Day! GO! GO! GO!” she yells, always taking pride in being his number one cheerleader.

And whenever Dejan glances at her in even the slightest of ways, he reminds himself of what she has been for him. His hero. Like Mom and Dad in one.

While Mom tops the list, Dejan has a few other role models.

There’s Dejan’s uncle, Chris Jones, the owner and operator of an auto shop in Hartford. In his younger years, Dejan would hang around the shop, sparking his curiosity in all the little complexities required to maintain a car. It’s his childhood dream to join the family business one day -- the main reason why Dejan plans to major in mechanical engineering.

|

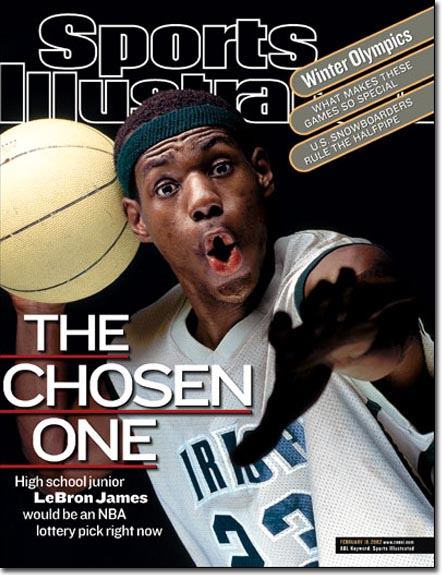

Derrick Rose went from youngest MVP in NBA history

to being shelved 8-12 months with an ACL injury. |

And there’s NBA MVP and Chicago Bulls point guard Derrick Rose. His hard work and dedication is the epitome of Dejan’s path to success—whether it be in sports or not. Dejan feels the tenuous connection between the two—Rose tore his ACL in Game 1 of a 2012 first-round playoff series versus the Philadelphia 76ers.

And like Dejan, Rose grew up without the presence of a father.

You can even see traces of the uniquely explosive, rugged and herky-jerky style Rose has branded in his four NBA seasons in Dejan’s game.

But as Dejan intends for it to be, his game on the basketball court – and off it – is just as diverse as his Haitian/African-American/Puerto Rican heritage.

On the court, he’s a slasher – a rim-runner who thrives in the transition game. While he may not look like much on the hoof – standing just 5’11” and weighing 155 pounds – he makes up for it with a ripped physique and outstanding leaping ability.

He’s often seen soaring above the trees for a rebound, smacking his right hand against the ball on his way down and taking off down court while weaving through a labyrinth of defenders for a basket – seemingly all in one motion.

In half-court sets, he uses his tight ball-handling ability – featuring a lightning-quick crossover mixed with exceptional foot speed and a series of ankle-breaking hesitation dribble moves – to blow by his defender and get to the rack.

And despite his prowess on the basketball court, he’s not a one-sport athlete.

In his freshman and sophomore years, he took advantage of his 4.48 40-yard dash time to be featured on the track team as a sprinter and on the football team as a wide receiver.

After focusing exclusively on basketball in his junior year, he planned to run track as a senior.

While most kids would try to blend in and imitate D-Rose, Kobe, LeBron or Kevin Durant, he doesn’t waste his time trying to be someone else. Just Dejan Frasier.

And if that means entering college and sitting out a year due to a medical redshirt, so be it. He believes persistence in his rehab process will bring him back stronger than ever.

But despite his inner-city tough kid approach, he still sometimes ponders what might have come to fruition if he stayed in Connecticut.

____________________________________________

|

Mark Mirko/The Hartford Courant

Anthony Jernigan (right) was named to the Hartford Courant's "Fab 15"

team after his junior year at East Hartford High. |

Dejan knows how his Connecticut friends did.

Ant Jernigan: Starred at East Hartford High School. Named an All-State performer in his junior season. Went on to play for Connecticut’s South Kent Prep – perennially one of the top basketball prep schools in the country – for his 2010-2011 senior season. Was part of a squad featuring current Philadelphia 76er Maurice Harkless as well as 2012 Jordan Brand All-American and current Providence Friar

Ricardo Ledo.

|

John Woike/The Hartford Courant

Jerome Harris averaged 18 points, 7 rebounds,

and 5 assists in his senior year at Weaver. |

Jerome Harris: Named all-state in his junior year. Transferred from East Catholic Prep in Manchester, CT to Weaver for his senior season in 2011. Led Weaver to a 16-8 record, the school’s best season since ’06-07.

Andre Drummond – Played for St. Thomas More – an all-boys boarding school in Oakdale, CT – for his final two years of high school. Led them to the National Prep Championship on March 9, 2012. Finished his senior year as the second-ranked college basketball recruit in the country by ESPN. Attended the University of Connecticut for one year before entering June’s 2012 NBA Draft, where he was selected 9th overall by the Detroit Pistons.

And Dejan? A different knee injury prior to the Dillon game meant he never got another shot against Marion. Waccamaw played Timberland in the first round of the playoffs. After hanging tough in the first half, the Warriors’ season ended in a 16-point defeat. Dejan watched in street clothes from the end of the bench. He was named to the Class AA All-Region VIII team at the end of the season.

Excuses can still be made. But Dejan knows he can’t go back to his days on that smooth court with Ant and Jerome at the Rawson Elementary school playground.

So he’s moving on.

Maybe that means wearing the green and gold of the USF Bulls.

Or maybe it means rolling under cars in a grease-stained blue jumpsuit.

And even while he works several hours bagging groceries at the local Fresh Market, he still sees a scholarship at the end of the tunnel.

Dejan knows things were lost between Pawleys Island and Hartford, but he isn’t concerned about where he may surface in a couple of years.

Because since the age of four, he’s had one constant in his life – basketball. It’s a hobby, an eraser, sometimes a lifestyle.

But most importantly? An escape. And he's not ready to turn the chapter on it just yet.

Wiggins has the body of a young Kobe -- a lanky two-guard with long arms and springs in his legs. Entering the NBA as an 18-year old, Kobe was 6'6", 193 lbs. Wiggins as a high-school junior? 6'7", 190 lbs.

Wiggins has the body of a young Kobe -- a lanky two-guard with long arms and springs in his legs. Entering the NBA as an 18-year old, Kobe was 6'6", 193 lbs. Wiggins as a high-school junior? 6'7", 190 lbs. Well the play still found its way there -- as the USA basketball team was in attendance, sitting against the wall behind the basket.

Well the play still found its way there -- as the USA basketball team was in attendance, sitting against the wall behind the basket.

Andrew stuffed the box score as a sophomore at West Virginia's Huntington Prep in 2011-2012, averaging over 23 points and 7 rebounds a game. He was named West Virginia's Gatorade Player of the Year and the MaxPreps National Sophomore of the Year. He also pushed Huntington Prep back in the national picture for the first time since '07, when O.J. Mayo (bottom right) led the state in scoring.

Andrew stuffed the box score as a sophomore at West Virginia's Huntington Prep in 2011-2012, averaging over 23 points and 7 rebounds a game. He was named West Virginia's Gatorade Player of the Year and the MaxPreps National Sophomore of the Year. He also pushed Huntington Prep back in the national picture for the first time since '07, when O.J. Mayo (bottom right) led the state in scoring.